It has been 365 days and they are still missing. A whole year has passed since global attention focused on Nigeria in the aftermath of the kidnap of female students sitting exams from the Government Secondary School in Chibok in Borno State in the North East.

This was not the first time girls and women have been abducted and it was not the last. What was different about Chibok was the number of girls taken and the global interest this sparked. The worldwide movement encompassed the unlikely combination of Nobel Peace Laureate Malala Yousufzai, the pop star Chris Brown, women in a Syrian refugee camp, Michelle Obama and, of course, women’s rights activists from across Nigeria. They demanded a serious, urgent and decisive response.

What has been lost in the narrative is that this movement was started in Maiduguri, Borno’s capital, by women who live with the conflict every day. A week after the abductions, these women called on the Nigerian government and President Goodluck Jonathan to take action. Their plea was simple: “If it were Jonathan’s daughters that have been stolen today, would the country go to sleep?” Their voices came from the heart of the conflict and in the face of great personal risk and fear of reprisals.

#BringBackOurGirls

A wave of protests took place across Nigeria and on social media calling on the government to #BringBackOurGirls. In Abuja, over 1,000 people, mostly women, marched in the pouring rain to the National Assembly to urge their representatives to act.

Protests were also held in Lagos, Port Harcourt, Kano and other cities around Nigeria.

Solidarity actions took place in cities around the world. Protesters, women and men of all different ethnicities and religions, gathered daily at Unity Fountain in Abuja to maintain pressure on the government. Women in the parts of north-eastern Nigeria most severely affected by the fighting and kidnapping had been organising already around previous cases of abduction. They intensified this, setting up services offering trauma counselling and advocacy for individual survivors. They reached out and rallied those within their communities that held power, such as traditional and religious leaders, to join the fight against the stigma and shame survivors often face.

Beyond hashtags

Living in Abuja and doing human rights, peace and security work, I experienced life in the eye of the tornado that was the intense media and political attention at the time. I was overwhelmed with requests for meetings from international NGOs, foreign government investigative missions and journalists.

Many seemed most interested in their own reputations and arrived in Nigeria with firmly-held preconceived ideas. I became profoundly disillusioned. My frustration was born out of the incomplete and twisted nature of the narrative being spun, in Nigeria and across the world. This was that the issue was about Chibok only, that it was about an easily demonised organisation they called Boko Haram (not actually their name but one given to them by the media) who had kidnapped more than 200 girls. Such abductions have taken place before and after what happened in Chibok in April 2014.

Little attention was paid to the women in the North East who had been negotiating for the release of kidnapped women and girls. Few noticed when women provided healthcare and psychological support for those who were released or managed to escape and others in their communities and spoke out about this on public radio and in other forums. This is in stark contrast to the horror and international attention and condemnation in the wake of the Chibok abductions. Services and assistance were focused solely on the Chibok community. Even when other abductions took place after April, if it wasn’t about ‘the Chibok girls’, people were not interested.

Even when other abductions took place after April, if it wasn’t about ‘the Chibok girls’, people were not interested

Then there is general prejudice. Nigeria occupies a strange place in the psyche of outsiders. Part fascination, part fear, people come to it full of preconceptions, thinking they know the country without having visited. Synonymous with 419 scams (such as the emails you receive promising untold millions – if you just send your bank details) and corruption, terrorism has been added to the many strings of Nigeria’s bad PR bow. Indeed there is only bad news ever coming out of Africa’s most populous nation: the heart of darkness for modern times.

Amid violence and kidnapping, aid shortages and hunger

Recently the violence in North East Nigeria has intensified. Jama’atu Ahlis Sunna Lidda’awati wal Jihad (JAS), commonly known as Boko Haram, carry out attacks on villages and communities on an almost daily basis.

Chronic underreporting and discrepancies between figures make it difficult to understand the scale of what is happening. The UN at the end of January reported approximately 981,416 people had been displaced across the country, of which more than 90 per cent are in the North East. Others estimate that over 1.5 million people have been displaced since the start of the fighting. People have abandoned rural areas in particular and flooded into the state capital Maiduguri, now bursting at the seams. Given the lack of camps for those displaced, people have been staying with friends, relatives and goodhearted people. I know of families living in chicken coops.

Acute food insecurity seems only months away. People have abandoned farms and agricultural activities due to the fighting, with predictable effect on the next harvest. Food stocks being depleted, people are resorting to eating grain saved for the next planting season. Markets have shut down.

Not only have people’s livelihoods in rural and urban areas been lost due to the fighting but there are now additional members (refugees from pillaged villages) of their household to feed – and food prices in Maiduguri are rocketing.

There is little humanitarian assistance being provided in the face of this escalating need, from the government or from the international community. In 2014, donors provided 17 per cent of the amounts needed for humanitarian work. The humanitarian crisis in Syria and elsewhere in West Africa, added to the perception that Nigeria is rich enough to cope without external support, are likely causes. Meanwhile, local communities try to cope.

The impact on boys and young men

Gender norms are significant in sparking, perpetuating and intensifying violence. This conflict has impacted men and women differently. The way that ideas of masculinity are used to perpetuate violence and drive recruitment is completely absent from analysis and debate.

It is significant, for example, that there is a social expectation that young people, men in particular, defend their communities and take responsibility for their protection. As reported by the Watchlist on Children and Armed Conflict, “If you are a man you must join. At 13 and 14 you can join, you are a man.”

The way that ideas of masculinity are used to perpetuate violence and drive recruitment is completely absent from analysis and debate.

Boys and young men are pressured to join groups by threats to their families and incentivised by cash. Such pressure is difficult to resist. Gender norms oblige men to provide ‘bride price’ and be the family breadwinner. Faced with these responsibilities and high rates of unemployment, joining JAS offers livelihood opportunities. This is especially so, when manhood is synonymous with aggression and power. Add to these ideas the notion of a man’s responsibility to defend the community, whether from the encroachment of Western ideas, or from the abductions and killing by JAS.

Kashim Shettima, the Governor of Borno, recognized these pressures on young men and boys. He said: “Yusuf [founder of JAS]… also arranged inexpensive marriages between sect embers, which enabled many of them to marry and gave them personal dignity and self-worth.”

Living with violence

When people think of women and North East Nigeria (if they think of them at all), they think of the abductions of girls from schools and, more recently due to a wave of attacks, young girls used as suicide bombers. These are issues that need urgent action but this is only a partial account of what is actually happening to women.

The conflict exacerbates existing inequalities and marginalisation. According to a 2007 Population Council report, 75 per cent of women who live in rural areas of the North East and North West had never been to school, 64 per cent of young women in the North East are illiterate and the median age of marriage is about 16-years-old. Women own just 4 per cent of the land in the region despite their involvement in subsistence agriculture and other farm activities.

The way the conflict has unfolded, with constant attacks on villages and local infrastructure, has led to the closure of health centres, both permanently and for extended periods of time. This has particularly impacted women: pregnant women are rarely able or willing to seek medical attention and instead look to traditional birth attendants, who often provide a lower quality of care and may engage in harmful practices.

The majority of those displaced by the conflict are women and girls. Of the estimated 87,000 refugees in Niger, 50 per cent are women and 45 per cent are children. Many women must cope with the disappearance, detention, execution and recruitment of their husbands by JAS and the security forces. They live with the uncertainty of not knowing what has happened, the trauma of loss and violence, and the reality of providing for the family left behind. The little aid that is there is given to (male) heads of households: when a man is dead or missing, this may go to his brother and not his wife. Many women, having lost their primary breadwinner, engage in street hawking and selling sex.

There is also a concerted attack on women’s rights and freedoms. Mohammed Yusuf, the founder of JAS, first called for women not to mix with men in schools at all. Then he said women should not attend schools. He later said that nobody should go to school if taught Western, rather than Islamic, education.

My friends in Maiduguri report JAS members threatening women in markets, telling them they should not be in public without male relatives. Women wearing ‘tight clothing’ and particular hairstyles are often killed during ambushes and attacks.

It is right to say that women’s rights, their bodies and freedoms in Borno, as in other countries, have been the battleground on which the war is being fought.

Why does JAS use kidnapping as a weapon?

It was in response to the government imprisoning their own wives that JAS fighters began abducting women and girls.

Following the arrest of over 100 women and children in 2012, JAS leader Shekau said, “Since you are now holding our women, just wait and see what will happen to your own women. Just wait and see what will happen to your own wives according to Shariah law, just wait and see if it is sweet and convenient for you.” The wives and children of soldiers were abducted from military barracks in Bama, an area in Borno, in December 2013 and the rate and scale of abductions has increased in the past 18 months. The following verse is used as Qur’anic justification to abduct so-called enemy women. “Also (forbidden are) women already married, except those (captives and slaves) whom your right hands possess. Thus has Allah ordained for you.”

Women and girls are being taken from schools, markets, during raids, public transport, during and after attacks on villages and on roads. On 12th December 2013, armed men along the Damboa-Biu road captured women on their way home from the bank. Young women have been taken from their homes at night or from the streets while hawking products. The kidnappers offer between N2,000 to N5,000 (between £7 and £17) to their parents as bride price. Then the women and girls are taken to camps where they are forced into domestic servitude, ‘marry’ fighters and to convert.

One of the women who escaped spoke about being raped repeatedly by 10 to 15 men a day, some young enough to be her sons. She was also ‘married’ to one of them. When tested for HIV, she found she was pregnant. Her husband “found it difficult to accept her back”. She became depressed and tried to commit suicide. It was only then that she was permitted to have an abortion. In Nigeria, abortion is illegal unless to save the life of the mother.

When people sent to protect become the bad guys

Another reality of the conflict is abuses committed by government forces and officials. The International Centre for Investigative Reporting found that hundreds of girls and boys had been kidnapped from refugee camps in Borno and had been trafficked, raped or sold as unpaid domestic workers.

A reporter from the Centre was offered children at a price of N50,000 (£165) each by officials from the government’s National Emergency Management Agency. The same journalist interviewed a 16-year-old girl who was promised a job helping the wife of a State Emergency Management Agency official. When she arrived at his home, there was no wife. The state official locked her in his home and raped her continuously until she managed to escape. A panel set up to investigate the incident has been given just one week to gather evidence and present findings.

I interviewed women’s rights activists in the Middle Belt of Nigeria for an earlier report and they told similar stories of the sexual abuse of women and girls by security forces. Sexual exploitation and abuse by armies is a problem worldwide, and while it has received greater international attention in recent years, there is still a culture of silencing and denial. When you raise the issue with officials, the reaction is either to reject it happens or acceptance with excuses such as, ‘What else can you expect? They’re so far away from their wives.’

Women as fighters

Women as victims and survivors of violence is just one side of the story. They are also active participants in both JAS and in groups aimed at stopping the sect.

There is a women’s wing of JAS made up of women and girls who chose to join or were forced to do so after being abducted. Although coercion is at play through the use of drugs, indoctrination and fear, at least some of these women are active agents who have chosen to join the sect. Gender inequality is tied to reasons why many women get involved. Academics Zainab Usman, Sherine El-Taraboulsi and Khadija Gambo Hawaja found in their recent research on radicalisation that societal and cultural expectations of women to depend economically on men leave them with few options when husbands or fathers leave to become active members of JAS or if they die. Without education and with little access to jobs, women have few ways to support themselves and their families. JAS gives money, food and other benefits to members and has a dedicated fund for widows of insurgents, in contrast to the lack of compensation or social safety net provided by the state.

Women as victims and survivors of violence is just one side of the story. They are also active participants in both JAS and in groups aimed at stopping the sect.

JAS also offers opportunities to women they do not have elsewhere. Women in parts of North East Nigeria typically face barriers in taking part in public life, but were able to participate in gatherings led by Mohammed Yusuf, the founder of JAS. He would also speak to them directly, albeit about how to behave and dress.

A desire to avenge the deaths of family members by security forces is also a motivating factor for women joining, especially given widespread detention without trial of anyone of fighting age and extrajudicial killings of those suspected (but not proven) to be part of JAS.

Women play the traditionally gendered roles of cooking, cleaning, companionship and providing sex (either voluntarily or through force). They transport weapons and money past security officials, gather intelligence and lure security forces into ambush, as they are less likely to be suspected than men. Three women caught with eight AK-47 rifles which they planned to sell, said they had no other choice given lack of sources of livelihood and that JAS was offering them N1,500 per gun.

Women are also instrumental in recruitment and training, particularly of other women, by using family and kinship connections. Indeed, marriage is a powerful tool to cement relationships of trust and loyalty to keep those already radicalised within the fold and used as a reward for joining. Honour accrues to families whose members have been martyred in the struggle and there have been reports of women urging their men into battle and using social pressure to persuade family and close friends to join.

Women and girls have also participated directly in attacks. In July 2014, female bombers carried out attacks in Kano. In July 2014, a 10-year-old girl was arrested carrying a suicide belt. In January 2015, a girl suicide bomber thought to be as young as 10 detonated a device near the main market in Maiduguri, killing at least 20 people and injuring many more. Teenage girls with AK-47s carry out attacks on communities such as that on Marte LGA on 10th July 2014. A student at the Federal Government Girls’ College in Taraba was found during a routine bed search with two grenades. A 19-year-old girl who escaped from a camp was interviewed on BBC Hausa about attempts to initiate her as a warrior. After they had killed four men, she was asked to kill the fifth. When she was unable to do so, the task was taken over by a woman fighter. Part of the responsibilities of active senior female JAS fighters is to oversee the integration of newly abducted women into camp life.

Not only are women active in JAS but they are also active in fighting against them. Young women and men, filling a vacuum caused by the failure of security forces to adequately protect communities, formed community self help groups, known as the Civilian Joint Task Force (JTF). The Civilian JTF is not above reproach: there have been a number of incidences of human rights violations, including sexual harassment of young women. People in the North East are worried that there may be a trend towards indiscriminate violence if care is not taken. However, they are also seen as the key factor stopping JAS taking over Maiduguri.

Although young men make up the majority of Civilian JTF members, women are also active due to their personal commitment to act and the outcry against men searching women at checkpoints. A young widow, who witnessed the killing of her relatives by JAS and was threatened with assassination for not wearing the hijab, started the women’s corps. When female JAS members began carrying arms to sustain the insurgency, women started checking fellow women, catching many trying to sneak past checkpoints with arms and ammunition. Women have been active in ferrying people out of occupied territories, including two who were caught and killed in front of other women last year. Women, such as Mai Bintu, the woman chief hunter of Bama, have also led the Civilian JTF on operations against JAS.

JAS has threatened to be particularly violent with female security and intelligence officials: “Whenever we catch any woman spying on us, we would slaughter her like a ram.” In 2013, a video was released of the beheading of a female security official.

Women as negotiators for peace

In addition to women’s roles in fighting on all sides, they are also crucial in keeping families and communities going. They have been finding new ways to ensure access to education despite closure of government schools.

Women’s rights organisations have been working with vulnerable and marginalised groups such as sex workers, hawkers, domestic workers, widows and survivors of sexual violence equipping them with life skills and linking them to microfinance bodies. They have been vocal in pressuring the government and traditional and religious leaders to take action. There have been multiple marches from 2009 onwards calling for peace and justice by women through the streets of Maiduguri in the midst of the conflict and violence.

Caught between security forces who commit human rights violations and JAS fighters who attack, kill and abduct, these women walk a narrow path to be seen as independent and neutral.

Women act as interlocutors and negotiators as they are more trusted than men with JAS and security forces alike and due to their contacts. They ensure safe passage for humanitarian and medical agencies to provide emergency care needed. They negotiate for the return of women and girls who have been abducted. Caught between security forces who commit human rights violations and JAS fighters who attack, kill and abduct, these women walk a narrow path to be seen as independent and neutral. As Barrister Aisha Wakil, one of the women trying to negotiate peace, says, ‘I’m just in the middle grasping for peace.’

They draw on a long tradition of women’s active participation in politics and state administration including during the time of the historical Borno Empire. This reality is in stark contrast to stereotypical images of north-eastern Muslim Nigerian women: victims of abuse, married off at an early age, in seclusion with little agency or power.

It’s complicated: the role of women in the conflict

Despite the active and pivotal roles women are playing as JAS fighters, CJTF members, security officials, to negotiate and build peace and fight for human rights and justice, the conflict is seen as between men. The clash is seen to be between young men in the army, young men in JAS and young male Civilian JTF members, with women only occupying the space of victimhood.

One year after the Chibok abductions focused the eyes of the world onto Nigeria, the epicentre of the international storm has moved elsewhere. Foreign media and politicians no longer talk about the Chibok girls. They are now concerned with Isis, Syria and Iraq.

Meanwhile, in Borno, the battles, physical, rhetorical, political and ideological continue to be fought on and over the bodies of women. They suffer violence and its short and long-term impact but victimhood and suffering is not the only story. Women are also active participants in the insurgency, in fighting against it, in resisting violence, helping others cope and in working for peace, justice and rights.

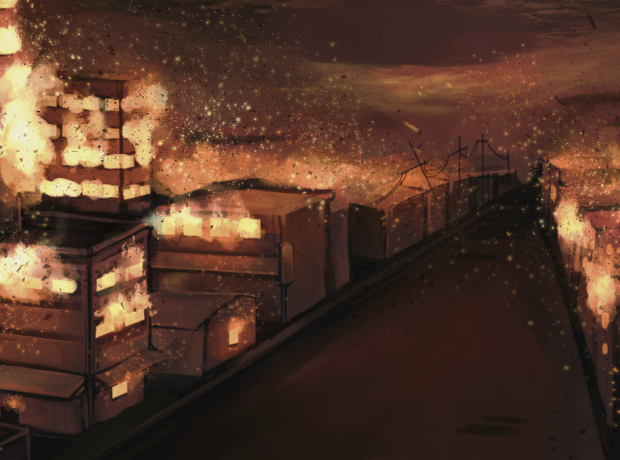

Photo by EU Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection